On 2 Jul 1916 Charles Harlington found himself in France where he fought for 181 days until on 29 Dec 1916 he was returned home suffering from

'trench foot'.

Trench foot is a medical condition caused by prolonged exposure of the feet to

damp, unsanitary, and cold conditions. The use of the word trench in the name of

this condition is a reference to trench warfare, mainly associated with World War

I. Affected feet may become numb as a result of poor blood supply, and may

begin emanating a decaying odour if the early stages of necrosis (tissue death) set

in. If left untreated, trench foot usually results in gangrene, which may require

amputation. If trench foot is treated properly, complete recovery is normal,

although it is marked by severe short-term pain when feeling returns.

Trench foot can be prevented by keeping the feet clean, warm, and dry. It was also

discovered in World War I that a key preventive measure was regular foot

inspections; soldiers would be paired and each partner made responsible for the

feet of the other, and they would generally apply whale oil to prevent trench foot.

If left to their own devices, soldiers might neglect to take off their own boots and

socks to dry their feet each day, but when it was made the responsibility of

another, this became less likely.

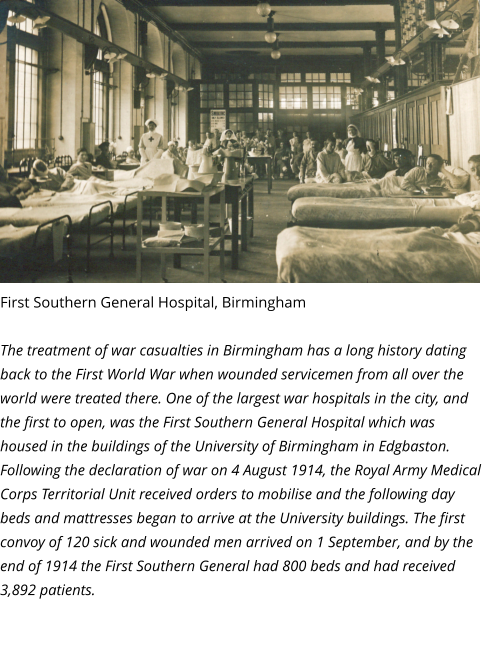

Charles was admitted to 1st Southern General Hospital, Birmingham on 30

Dec 1916. He spent 38 days, to 5 Feb 1917, in hospital after which he was

discharged fit for duty. He remained on home soil until he was returned to

France on 7 Apr 1917 to fight on the Western Front.

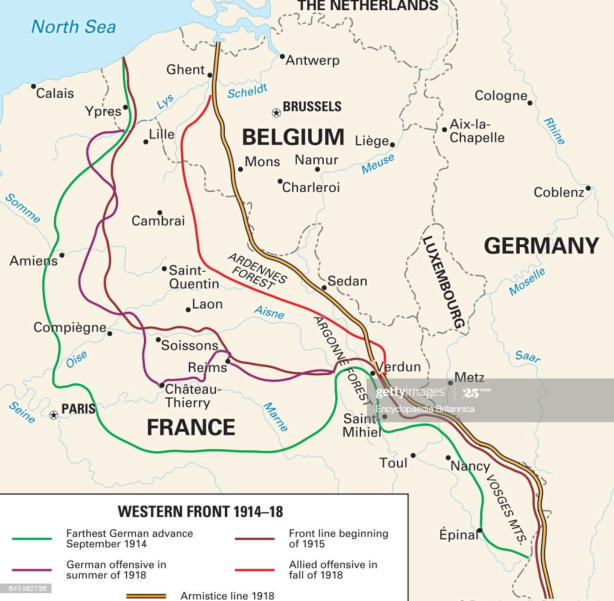

The Western Front was the main theatre of war during the

First World War. Following the outbreak of war in August

1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by

invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military

control of important industrial regions in France. The German

advance was halted with the Battle of the Marne. Following

the Race to the Sea, both sides dug in along a meandering line

of fortified trenches, stretching from the North Sea to the

Swiss frontier with France, which changed little except during

early 1917 and in 1918.

Between 1915 and 1917 there were several offensives along

this front. The attacks employed massive artillery

bombardments and massed infantry advances.

Entrenchments, machine gun emplacements, barbed wire and

artillery repeatedly inflicted severe casualties during attacks

and counter-attacks and no significant advances were made.

Among the most costly of these offensives were the Battle of

Verdun, in 1916, with a combined 700,000 casualties

(estimated), the Battle of the Somme, also in 1916, with more

than a million casualties (estimated), and the Battle of

Passchendaele (Third Battle of Ypres), in 1917, with 487,000

casualties (estimated).

To break the deadlock of trench warfare on the Western Front,

both sides tried new military technology, including poison gas,

aircraft, and tanks. The adoption of better tactics and the

cumulative weakening of the armies in the west led to the

return of mobility in 1918. The German Spring Offensive of 1918 was made possible by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that ended the war of the Central Powers

against Russia and Romania on the Eastern Front. Using short, intense "hurricane" bombardments and infiltration tactics, the German armies moved nearly 100

kilometres (60 miles) to the west, the deepest advance by either side since 1914, but the result was indecisive.